Ukraine's proposed legislative amendments raise concerns about the future of freedom of speech and the free flow of information.

BACKGROUND

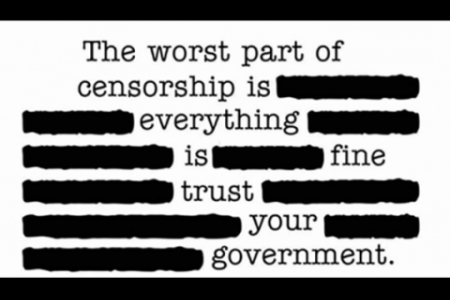

In the 21st century, when critical thinking and analytical skills are so important to consume truthful information, it is worth questioning why some governments resort to strengthening controlling mechanisms rather than promoting digital literacy and the free flow of information. In the case of Ukraine, the government proclaims the latter to be detrimental to national security, subsequently justifying stricter control over the information space and online activities of its citizens.

In November 2019, the President of Ukraine mandated the former Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports to prepare a draft law, which should, inter alia: specify news standards; envisage mechanisms for prevention of disinformation dissemination; and strengthen the liability for violation of the legislation in the information field. In January 2020, the Ministry presented the first draft as a bill introducing amendments to certain legislative acts of Ukraine with regard to ensuring national information security and right to access to reliable information. Unsurprisingly, the released draft led to a lot of public criticism.

Rather than adopting standalone new legislation, the Ukrainian legislative practice has shown that the best way to lobby an unpopular idea into a law is instead to introduce new amendments to a number of other existing legal acts. And the larger the number of such legal acts subject to amendments, the less obvious is the ultimate goal of the authorities, not only for a lawyer well-versed in these issues, but even more so for ordinary citizens. Furthermore, choosing an eloquent title for the bill that refers to national security is a sure choice for its smooth adoption in the country, which is suffering from an armed conflict for six years in a row. Would anyone object that information security and reliable information are crucial in a democratic society in the digital age? Unlikely, unless they carefully read the text of the draft law and found the devil in the details. Let’s take a look at those details.

DISINFORMATION AND EVERY CITIZEN AS A JOURNALIST

It all starts with unreasonably broad definitions of misinformation and disinformation, determining the first as false statements about persons, facts, events, phenomena that are either nonexistent or existent, but statements about which are incomplete or distorted; and the latter as misinformation regarding the issues of public interest, in particular national security, territorial integrity, sovereignty, defense capability of Ukraine, right of Ukrainian nation to self-determination, citizens’ life and health, and the environmental situation. Basically, everything that would be against official government discourse could be, with these definitions, easily classified as disinformation, with the consequences being huge fines and imprisonment. However, the rules are not without exceptions, and the authors of the draft law sweetened the disinformation bill by excluding the following from the definition of disinformation: value judgements, satire and parody (if the disseminated information was clearly announced as such), and unfair advertising.

According to the draft law, every person collecting, receiving, creating, editing, or disseminating mass information automatically becomes a journalist. And information becomes defined as “mass” once it is determined to be available for an unlimited or indeterminate number of persons, or when it can be accessed by any person from any place at any time. This alone gives enough food for thought to owners of public social media accounts and even those with private profiles who make some of their posts public. Sharing mass information would become a responsible task that requires dissemination of only reliable information upon the completion of respective fact checks. Publishing a hyperlink to an information source would grant immunity from the responsibility for sharing misinformation. However, the draft law remains unclear as to what will happen to those who would not simply share a link, but would add a comment or make a short summary of the shared article.

Moreover, individuals and legal entities are obliged to provide their identification data and contact details (by publishing them on website/webpage, social networks, messengers, etc.) every time they share mass information. This is a sure sign that the era of anonymity is coming to an end. The government has created additional regulations to ensure that no one escapes from the “all-seeing eye” by obliging hosting providers, social media platforms, and messenger services to appoint a representative or open a representative office in Ukraine. Upon request they would be required to provide identification data of the owners of websites, webpages, accounts, channels, chats, or other groups with more than 5,000 subscribers or unique daily visitors, and owners of open channels.

BUT NOT ALL JOURNALISTS ARE EQUALLY PROFESSIONAL

At the same time, the draft law recognizes a special caste of professional journalists to be differentiated from regular journalists by their membership in a professional association and the execution of their duties on a permanent and professional basis. The state generously grants journalists a right to self-governance but a very specific, state-designed type of it – through the Association of Professional Journalists of Ukraine that can’t be restructured or liquidated at any point. Moreover, the Association’s decisions will be binding upon its members. To make the establishment process as smooth as possible, the state even defined what organizations are entitled to participate in the Association’s constituent meeting. Membership in the Association will be proven by a press card and conditional upon factors such as Ukrainian citizenship (or permanent residence permit), three years of professional journalistic experience, and adherence to the Code of Journalistic Professional Ethics. Basically, if journalists do not agree with the law’s prescribed self-governance model and do not want to become a part of it, they would not be considered as representatives of the profession and would not receive any guarantees from the state. The choice, then, is not really a choice, but the right to freedom of press does not seem to bother the authors of the draft law.

Only professional journalists would be granted accreditation to closed meetings conducted by state and local self-government authorities, as well as allowed to collect information in war zones, emergency, and mass riots areas. Similarly, only professional journalists would be entitled to guarantees against investigative actions that might pose a huge threat to freedom and life of those journalists who might not join the state imposed Association and would prefer to preserve an independence of journalistic integrity. A chilling effect can be equally created by the obligation of journalists to notify their supervisors or persons in charge of editorial control of any potential lawsuits or any other legal claims that might arise in a response to the publishing of specific information.

INFORMATION COMMISSIONER AND TRUST INDEX

The state control wouldn’t be complete without a specifically entrusted watchdog with a very human rights oriented title – Information Commissioner. The proposed Commissioner would be appointed by the government of Ukraine for five years (with a possibility to be reappointed for one more term) from among candidates nominated by the Parliamentary Human Rights Commissioner, the Ministry of Justice, and the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports (considering that the Ministry was dissolved afterwards, this function will most likely be given to its successor). As a result, claims that the Commissioner is fully independent from any other state authorities and public officials are inconsistent with the fact that the position is filled directly by the government. The government’s authority to create this type of position is also quite dubious. The powers of the Commissioner are too broad to be impartially handled by a single person without any checks and balances. These powers vary from requests for a response to or refutation of disinformation; filing lawsuits if the information is determined to be disinformation; and limiting access to disinformation shared online or to whole websites, webpages, and user accounts in messengers. Moreover, the Security Service of Ukraine is obliged to assist the Commissioner in obtaining evidence of violations of the law, including in cases of disinformation dissemination.

Despite the fact that the draft law requires the creation of positions of the Commissioner’s representatives, it is difficult to imagine how big the staff should be in order to provide non-stop monitoring of all information and to make a reasonable and well-grounded decision about whether or not such information constitutes disinformation. It is a daunting task that could lead to selective monitoring, which is far from being transparent, or could result in total surveillance and censorship. The very idea of thorough monitoring of information flow is a very dangerous attempt to create a modern version of a police state.

One of the new duties entrusted to the Commissioner would be a trust index aimed at rating mass information disseminators based on the reliability of distributed information. A certificate of compliance would be issued by independent organizations. However, the criterion of independence seems to be used exclusively for creating an impression of credibility, which in practice is doubtful given that such organizations will be selected at the sole discretion of the Commissioner. The corresponding trust index certificate of compliance would be issued upon payment of a fee, and is valid for a year. Applying for the index is optional, but once approval is received all information materials of the respective media outlets will be marked with this “quality sign”. While it might look like a truly democratic process, it isn’t. Instead of promoting media diversity and investing into digital literacy, the government would simply point “ignorant citizens” to information carefully crafted by media loyal to the government. Recognizing the state as an official guardian of truth is not acceptable in a democratic society that should promote diversity of opinions and media. What is really scary is that a political establishment that came to power on the wave of an extremely successful digital campaign is now openly advocating for the state to be the ultimate arbiter in deciding what is true or false, and criminalizing everything that people in power don’t like.

RESPONSIBILITY

According to the draft law, the author and the disseminator of misinformation bear joint responsibility. Intermediary liability (i.e. when a third party communications platform or provider is held liable for its users’ content) is stipulated in cases when none of the above can be identified. This contradicts an internationally recognized principle that Internet intermediaries should be exempted from liability in all cases except for those when they explicitly participated in modifying the third party content. The draconian amounts of fines seem to be meant to fully silence any critical voices. For example, a fine for disinformation dissemination (starting from the third case during the same year) subject to voluntary refutation of the content in question constitutes 4,723,000 UAH (approx. $169,000 USD) and without refutation – 9,446,000 UAH (approx. $338,000 USD). At the same time, two to five years imprisonment is enshrined in the draft law for using bots to systematically disseminate deliberately false information about the facts and events constituting a threat to national security, public safety, territorial integrity, sovereignty, defense capability of Ukraine, right of Ukrainian nation to self-determination, citizens’ life and health, and the environmental situation. In other words, it is an attempt to criminalize the spread of information the government deems to be false and potentially dangerous for itself.

CONCLUSIONS

The draft law has received enormous resistance from the civil society and journalistic community, and has been heavily criticized by international organizations, in particular the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Representative on Freedom of the Media, the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine, Reporters Without Borders, the Council of Europe, and the European Federation of Journalists. Moreover, the OSCE promised initiating a legal review of the draft law. It is noteworthy that the Parliamentary Committee on Humanitarian and Information Policy that would be in charge of reviewing a draft law once it is registered with the parliament has already issued a statement expressing concerns about the detrimental impact of the bill on freedom of expression in Ukraine. Additionally, the Committee expressed its readiness to provide detailed analysis of the draft law and to be engaged in its further iterations. In its analysis, the Council on Freedom of Speech and Protection of Journalists under the President of Ukraine noted that the draft law does not meet the proclaimed aim of countering disinformation, but significantly restricts freedom of expression, promotes self-censorship, and limits journalists’ rights. Thus, the Council stressed the inadmissibility of adopting the law in its current version and called upon the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports to refrain from submitting a draft law for the consideration by the government as such that does not correspond to the Constitution of Ukraine and international best practices.

Initially, the Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports in charge of drafting the disinformation bill was very positive about its adoption and announced a plan to submit a document for the government’s consideration in February with its subsequent registration in the parliament in March. However, after a wave of criticism the former Minister acknowledged that the draft law is undergoing only the first stage of public discussion, which will be prolonged in order to address all concerns expressed by various stakeholders. This statement was followed by dissolution of the government in early March. The Ministry itself was divided into the Ministry of Youth and Sports, and the Ministry of Culture, with the latter still awaiting appointment of a chief. With these changes, as well as due to the overall situation with COVID-19 pandemic, the fate of the bill was put on hold.

After huge public resistance, Ukrainian citizens can only hope that the draft law becomes history and never makes it to their future. And moreover, with the public’s distracted attention focused on keeping families safe and healthy during the COVID-19 pandemic, that the situation won’t be used by the parliament to vote for amendments that are unpopular and threatening to freedom of speech.

- Log in to post comments