When we start to think of digital rights as human rights, it transforms digital inequality into an issue of injustice. As the internet becomes a public utility that shapes our social, political, and economic lives, we have to think about what it means to be disconnected, who is entitled to meaningful connectivity, and how justice can be procedurally administered.

I never dreamed of a career in digital rights. My childhood did not include access to broadband, and even when I had my first job at an internet café, connectivity felt like a privilege. Now, in Zambia where I live, mobile internet is the means through which a majority are connected, and in the years since that first job, I have used the internet extensively to champion for girls' safety through blogging and online activism. However, despite my work as a digital rights practitioner connecting local communities to internet governance, meaningful connectivity still does not feel like a right that is legally guaranteed.

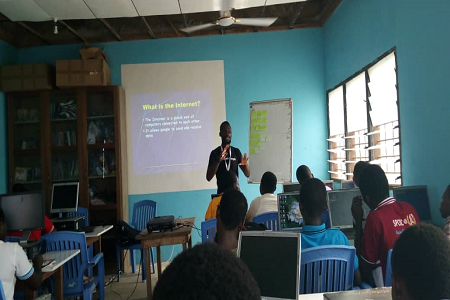

Much of the debate and discussion around connectivity is centered in the Internet governance space, which comprises a vast number of issues and stakeholders. When I participated in the Internet Society Youth@IGF program in 2017, it changed my perception of the role I could play in shaping the future of the internet. However, it remained unclear to me, how the discussions, policies, and projects happening at a high level would make a difference in my community. I wondered when the results of these activities would trickle down to my corner of the world. Who is responsible for this? Who do I call to get meaningful connectivity in my community?

The makings of an answer came to me while studying technology and justice at the London School of Economics as an Atlantic Fellow for Social and Economic Equity. I was fascinated by the linkages between technology and justice. Could digital inequalities be an injustice issue? And if yes, can there be reparations? From who, and how? During the course of my academic research, I came across a paper by Nancy Fraser on “Abnormal Justice,” which gives us a new way of framing justice in an increasingly capitalist and globalized world. I believe this concept can show us a new way of framing digital inequalities in a way that centers the most underrepresented groups online.

In traditional justice frameworks, Fraser argues that powerful states and elites typically resolve justice issues in a "smoke filled back room" that discourages open, democratic contestation. This inherently leaves those outside of a particular geographic or political jurisdiction out of the conversation. We see this happening today with US-based tech companies, who are outside of the legal jurisdiction for injustices committed in the Global South. This includes concerns of misrecognition, status hierarchy, misrepresentation and political voicelessness online. This power imbalance is a backbone to digital inequalities, and requires a new way of framing in order for an equitable internet to exist. However, in an abnormal justice framework, everyone who is subjected to the governance structures that regulate social interaction deserves to be heard and considered in governing and resolving disputes. When this is not the case, the most marginalized in the new digital world order have no say to what is right, what is fair, and what is just.

With the UN’s declaration of the internet as a basic human right, it is time to update our vocabulary around “justice” as it applies in today’s rapidly globalizing and capitalist world. Fraser’s model of abnormal justice offers a framework for creating a new shared understanding for the digital space, by asking three key questions: What? Who? How?

- What? What does equality online look like? Given the globalized nature of the internet and its increasing dependence on the private sector, how can we assert that our current internet landscape is what it should be when there is nothing to compare it to?

- Who? Who counts as a subject of justice in digital inequalities? Whose needs deserve consideration? Who belongs to the circle of those entitled to equal concern? Who is ‘justice’ supposed to protect and defend – and based on ‘what’ right?

- How? How can justice be procedurally administered when there is a contestation of justice, once the injustice has been identified? Where can one go to complain about digital injustice on a borderless internet, and how can equity online be defended?

The answers to these questions need to remain flexible in order to adapt to the often rapidly shifting nature of the Internet landscape. However, they can serve as key considerations for those looking to solve digital inequalities and cementing access to the internet as a human right.

What Does This Mean for Digital Rights?

Digital inequality affects the economic, cultural and political dimensions of our lives. When viewed through the lens of abnormal justice, unequal distribution of resources and class inequalities count as injustices. Implementing digital rights as a human right through the lens of abnormal justice creates a pathway to hold individuals, big tech and governments accountable for their actions (or lack thereof) on the internet.

Equitable decision making in the digital rights space and the internet governance community must both be part of both the consultative process, as well as in the implementation and enforcement of policies. In order to truly address the current injustices related to meaningful connectivity, we must find innovative ways for understanding the changing nature of the digital landscape. The theory of abnormal justice, for me, offers a roadmap to make internet governance more open and democratic.

- Log in to post comments