What happens during a national health emergency when citizens don’t have access to the internet? People in Venezuela are finding out as the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed and amplified government failures to expand access to the internet, which is often the only channel to get independent and accurate reporting.

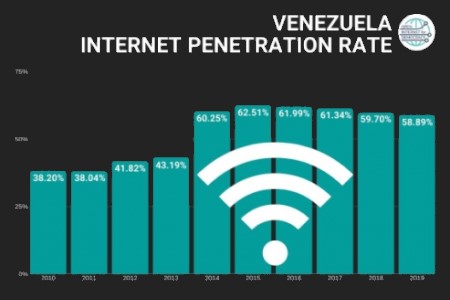

Whereas in most other countries internet penetration rates continue to rise year over year, in Venezuela the rate has actually fallen for the past four years. From a peak of 62.51 percent reached in 2015, internet penetration dropped to 58.89 percent by July 2019, which is the most recent date for which we have updated data published by the National Commission of Telecommunications (Conatel in Spanish). While a drop in internet penetration of just 3.62 percent may seem relatively minor, in the context of the current COVID-19 pandemic, we now see that its social consequences are actually quite significant.

A number of people who previously had access to the internet are now finding it more difficult, if not impossible, to connect. This includes administrative employees whose primary internet connection was at their offices, elementary school teachers who depended on the internet at their schools, and young people who went to internet cafes to be online. Few of them have a home internet connection now: in the context of COVID-19 where people are being encouraged or even mandated to stay at home, they no longer have the access to the internet that they once enjoyed.

Given that most newspapers are aligned with the ruling United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV in Spanish), and that private television companies and radio stations face great restrictions on the news they are able to broadcast, the internet is often the only way for citizens to access independent news and reporting. For example, citizens often rely on the internet to find out the price of the US dollar—the country’s reference currency—or to learn about the perspectives of opposition parties.

Those who do not have a home connection are, in many ways, cut off from what is going on around them. Internet inequality has become more visible and pronounced amid the pandemic, but some of the underlying causes far predate the current challenges.

Economic recession stifles infrastructure investments

Venezuela has been in an economic recession for seven years and has been experiencing hyperinflation for the past two years. For example, consumer prices rose 80% in April, according to the opposition-controlled National Assembly, while shoppers in various cities reported seeing some food items, such as cartons of eggs, doubling in cost. Ultimately, this economic turmoil has been a primary factor in declining in internet penetration rates.

In Venezuela, telecommunication companies must request government authorization before increasing their monthly rates. However, obtaining this government authorization to raise prices for internet service has been taking place at a much slower pace than the rise of inflation. The consequence is that today the monthly internet connection fee of the major internet providers in Venezuela is between 1 and 3 US dollars. For reference, that is less than what a 16-ounce bag of coffee costs at the supermarket.

This low and outdated monthly service fee has become a disincentive for companies to add more customers, provide quality service, and resolve network or wiring failures that have become more pervasive since 2015.

In their report Public Policies for Internet Access in Venezuela, researchers Raisa Urribarrí and Marianne Díaz point out that, in effect, private companies are forced to invest to maintain and improve their internet service platforms without being able to charge what it would cost to actually do so. Thus, they ended up being unable to satisfy a demand that, paradoxically, only grows with low monthly service fees.

The gap between the rate charged by the country’s private internet service providers and the money they need to buy new equipment and invest in the networks also affects the largest state-owned home internet service provider, the National Telephone Company of Venezuela (Cantv in Spanish).

Without the inflow of oil revenues, which have also plummeted amid the economic downturn, even the Venezuelan state ran out of financial resources to continue the infrastructure investments needed to expand the penetration rate in Venezuela.

Rural regions lack quality internet access

The economic crisis diminished infrastructure investment throughout the country, and this has had an especially dramatic impact in the most remote and rural parts of the country. While the national average internet penetration in Venezuela stood at 58.89 percent in July 2019, it becomes clear, when we look closely at the state level, that the situation varies greatly between the capital of Caracas and the regions in the interior of the country.

In Caracas, the penetration rate in July 2019 was 107.32 percent. This means that most of the 2.9 million inhabitants of the Caracas metropolitan area have at least one smartphone with Internet access, while the situation in the interior of the country is very different.

For example, nine of Venezuela’s states have internet penetration rates that are below 40 percent. Amazonas (17.48%), Apure (26.60%), Sucre (32.02%), Yaracuy (33.32%), Delta Amacuro (33.44%), Trujillo (35.29%), Guárico (35.42%), Falcón (36.05%), and Portuguesa (37.46%).

While the difficult terrain in many of these rural provinces can account for some of the difficulty in providing internet connectivity, it is clear that there is a vast disparity between urban and rural internet access in Venezuela. Thus, more must be done to address this massive digital divide within the country.

Conclusion

Without a doubt, the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the woefully inadequate internet penetration rates in Venezuela. At a time when people need access to reliable information the most, the data make it clear that for all too many this is nearly impossible.

And while the trend in internet penetration is currently still going in the wrong direction, we already know what it will take to turn this around. It will require a strong new public investment in the fixed broadband system throughout the entire country—including rural areas. Additionally, it will entail creating a legal and economic environment that provides security for private companies so they can refocus on providing the best possible internet service. Only when these policies are in place will we be able to get back to achieving the ultimate goal—making the internet available to all Venezuelan citizens as part of their fundamental human right to access information.

- Log in to post comments